In April 2016 a small team of 4 (two professional guides and two polar novices) will embark on an expedition from the southern tip of the world’s largest island, Greenland, to its unvisited northern coast. The team aims to travel some 2,000km over Greenland’s desolate ice cap, the 2nd largest in size after Antarctica, harnessing the power of wind using foil kites to propel them over the vast distances required to achieve their ambitious goal.

With a window of only 40 days to travel this vast distance, the usual means of polar travel, man hauling, is not even a consideration given the daily mileage that needs to be attained. Using the latest foil kite technology, coupled with several weeks of rigorous training in northern Norway it is the teams hope that they will be amongst a handful of polar adventurers that not only have covered such a vast distance, but delved into the relatively unknown northern shore of this vast polar wilderness.

Unlike man hauling, the process of using skin-mounted cross country skis to pull the expedition sledge (also known as a pulk) in conjunction with kiting, one can cover far greater distances due to increased speed of travel coupled with decreased energy expenditure. This technique also has a net effect of reducing the load in the pulk reducing the use of fuel and with a shorter expedition time frame less food is also required. The disadvantage is the reliance on the wind and the requirement of a high level of competence to operate equipment safely and efficiently in Polar conditions. There are a number of types of kite systems that can be considered, but for this expedition the team will be using Foil Power Kites, also called Traction Kites, which rely on the wind to propel the rider and the equipment. A variety of different sized kites are used to accommodate a variety of wind strengths, different snow conditions, changing weight loads and the individual’s skill and fitness level.

Despite the presence of two experienced guides, an expedition of this nature is not something that can be undertaken without a vast amount of preparation, education and training as all the team members need to be fully competent in all the numerous disciplines required for a trip of this magnitude. Therefore a time frame of 15 months is required before embarking on Expedition Margot in April 2016. Given the relative unknowns in entertaining such a feat with two team members who have yet to try themselves in the polar arena, the final route taken will only be decided once the guides are able to assess the team’s potential after initial training. It is hoped that, if all things go to plan that the chosen route will have never actually been attempted before.

There are a number of risks and complications that Expedition Margot will need to overcome during their crossing of this vast wilderness. The team will be under continual physical and mental stress for up to 7 weeks, relying solely on each other’s company and equipment they can fit in their expedition pulks. Greenland’s ice cap is an inhospitable place with continual sub-zero temperatures, relentless katabatic winds, endless horizons of white featureless terrain; physical hardship and mental fortitude are needed to overcome these obstacles if they are to achieve their most ambitious and impressive of goals.

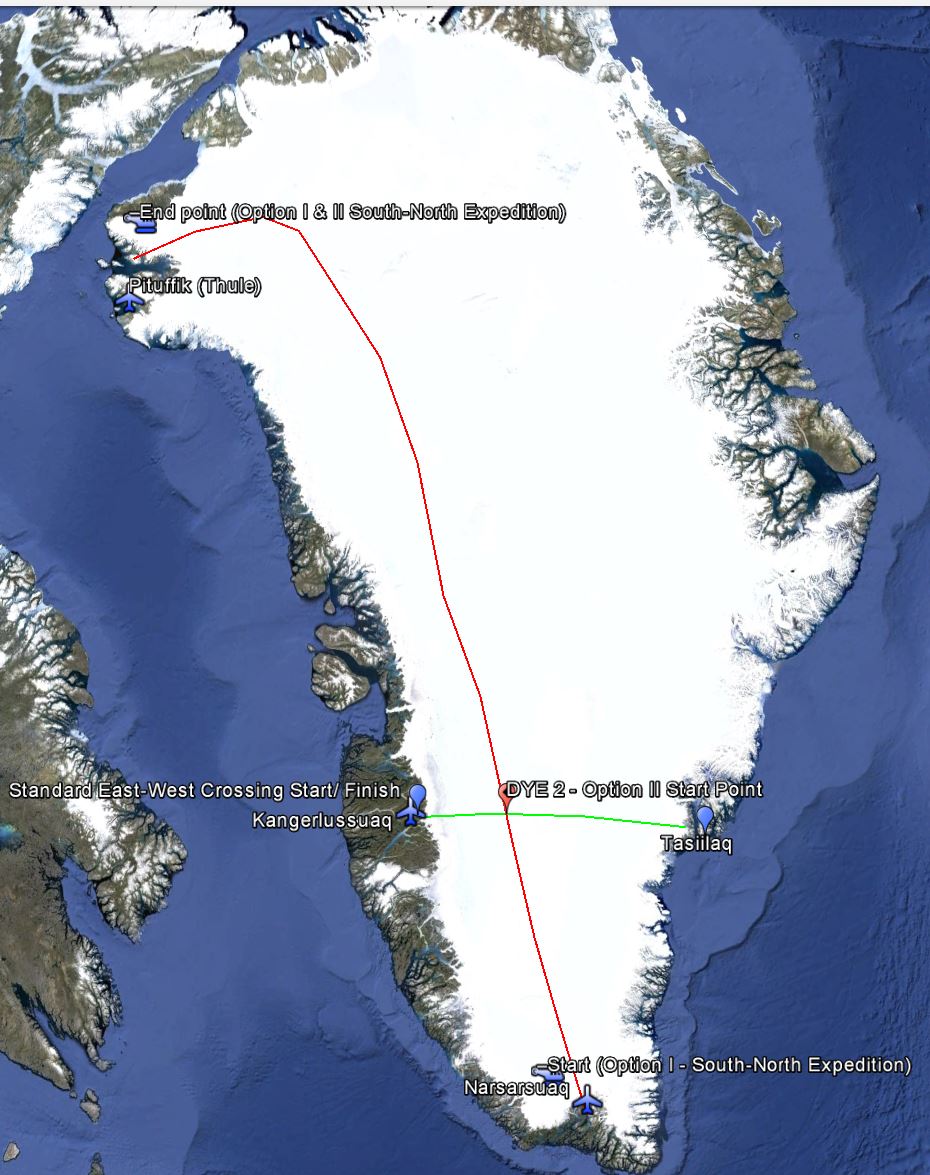

Greenland 2016 Route Map

Team member Henry Cookson has highlighted some of the risks and complications that could be encountered below.

Frost Bite & Cold Weather injuries

Given the temperatures we will experience there is always the possibility of injury from the cold, namely hypothermia or frostbite. We mitigate against this a number of ways.

During the training months Expedition Margot will carry out good, solid training in cold weather scenarios to help understand how to deal with the cold and use your clothes systems and equipment in the correct manner. It is important to train as a team so that the members can work out the division of labour, read fellow team members mood/ way of dealing with situations. Throughout the training periods the skills needed to effectively use these systems will develop and adapt to suit the individual in the various scenarios - sleep, exposure to the cold in and around camp, and whilst kiting. Crucially the team member will also learn how to monitor their situation and detect the warning signs and situations that could lead to hypothermia or frost bite.

By being well fed and well rested the chance of a cold weather injury is hugely reduced. Not only does an individual become less aware of a problem when stressed or tired, but the body itself is more susceptible to hypothermia or frost bite. Good tasting and well prepared food lends to everyone taking on the necessary calories - food is the fuel that fire the bodies furnace, producing heat and energy. We also have a very rigid system of regular rest/ snack breaks during travel to make sure people hydrate with warm drinks and eat. This also gives us a chance to access each other’s mental and physical state as whilst kiting there is little scope for communication.

Normally cold weather injuries are brought on by people pushing for an unrealistic goal - expedition goals brought on by the quest of “firsts” and world records can lead to unrealistic goals, too big a distance to cover in allotted time resulting in exhaustion and stress, or the sacrificing of food and equipment to save weight meaning the necessary calories are not consumed etc.

Having kites does have advantages and disadvantages in terms of the cold. The disadvantage is that during travel feet can get colder easier due to the relative lack of movement in the legs as opposed to man hauling. To mitigate against this, special systems for insulating our boots can be used as well as wearing the correct clothing on our torso - it is actually the bodies core temperature that dictates the susceptibility of frost bite to the extremities, and whilst a good boot or glove system is essential, that system becomes less effective if the heart is pumping cooler blood to your extremities.

Separation & Storms

The biggest concern is the possibility of the group being separated during travel. With the rapid pace of travel during kiting and the weather, especially in the south, being so unpredictable the situation could rapidly get out of control. To prevent this we adopt very strict travel formations and discipline. On top of this, with two guides, one to lead, the other to follow up results in a safety net for the other team members. In any event, critical equipment is split up so everyone carries sufficient resources to be self-sufficient, along with spare items like one-man tents, food, fuel, shelter and some form of communication to the outside world.

Storms can materialise quickly, and the infamous Piteraq (a katabatic wind which consist of cold air descending rapidly down the ice cap gradient) can rise suddenly and with fury. This has proved fatal to people in the past and not something to be complacent about. With wind speeds sometimes reaching beyond 160km/h strict precautions need to be in place.

Crevasses

There is relatively little danger of crevasses high on the icecaps flat plateau, but on the edge of the ice cap there is always this hazard to be vigilant of. . Depending on where exactly we are inserted/ extracted will influence the level of this danger, although our intended route largely avoids this, the potential arrival of an earlier than usual spring thaw will increase this risk. Irrespective we will take lightweight crevasse rescue equipment to mitigate against this. Naturally training for this will be practiced.

Wildlife

On the coast and the very edges of the icecaps there is always the possibility of encountering polar bears. Permitting requires us to carry a firearm anyway, and will be useful in case we have to descend the icecap by foot. There are other deterrents that can be deployed such as trip wire flares, flare guns and bear sprays. High up on the icecap, where the majority of the trip will take place, evidence of polar bears is virtually non-existent.

Expedition Margot is expected to take approximately 40-45 days to complete and we will be documenting the progress from now until they land safely back on UK soil during May 2016.